I went on a roadtrip to investigate T-Mobile’s coverage map

April 11, 2022, 8:00 a.m. ET

It was 11:54am on January 1, 2021, and I was parked at a Micro Center in Brooklyn. With my laptop wedged between my knee and the steering wheel, I was putting the finishing touches on a device that, once completed, would connect to my phone and record my cell service as I drove across the country. I was about to begin a six-week road trip during which I would hike, ski, visit friends and family, and explore. As I was planning the trip nearly two months earlier, I had an idea.

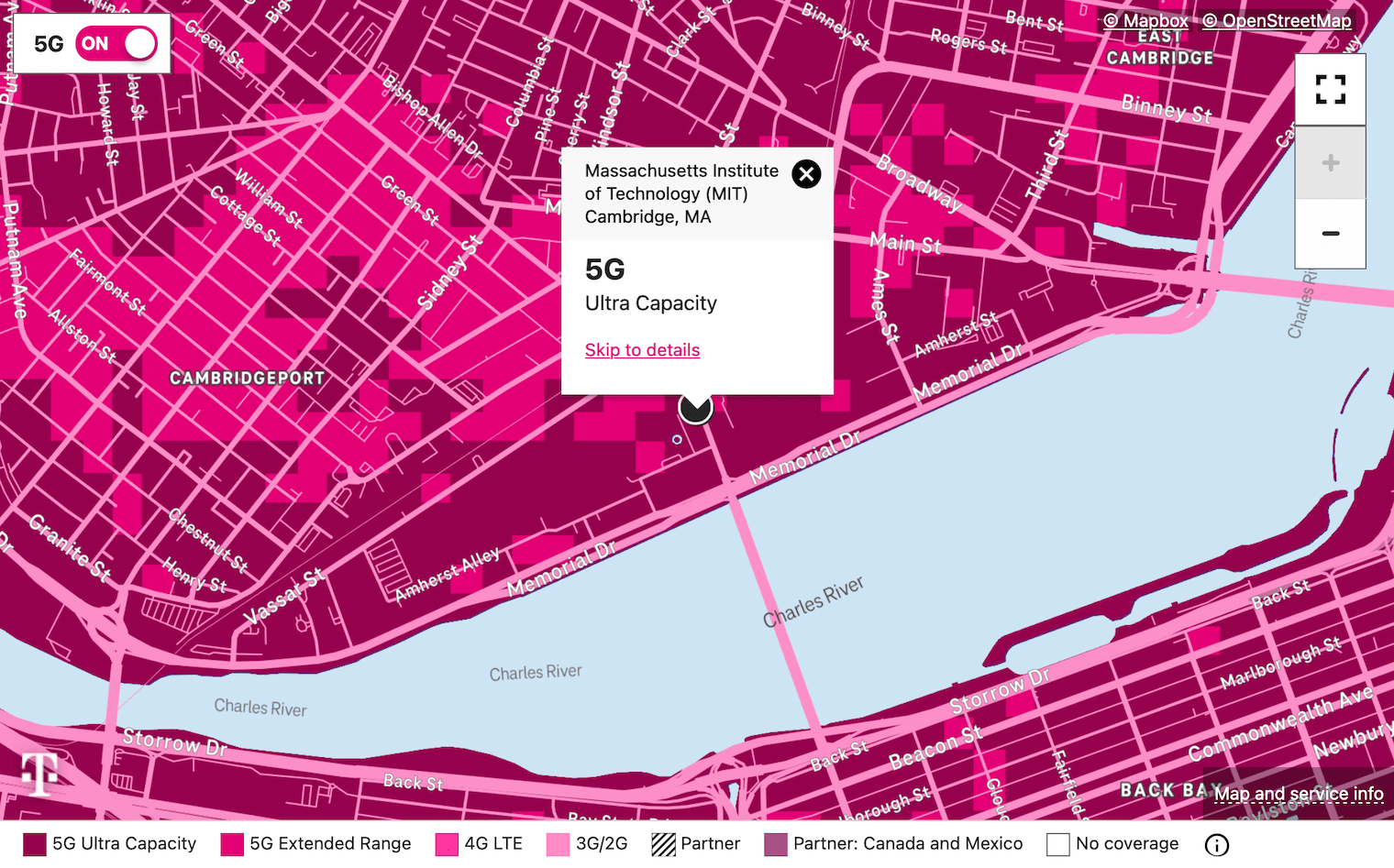

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been frustrated by the service provided to me by T-Mobile. Whether I’m in my room, hiking in the woods, or walking around downtown Boston, I can never seem to use the Internet when I need it. I’ll open the Mail app, tap on an email, and… nothing. “This message has not been downloaded from the server.” I’ll go back to my apartment in Cambridge, check the T-Mobile coverage map, and see what my coverage should have been wherever I was. “5G. Ultra Capacity.” Right.

Was I just getting unlucky? Or was T-Mobile’s service actually far worse than advertised? The scientist in me had to know. If I could collect a large sample of T-Mobile coverage data, I could compare my experienced coverage to the coverage advertised on their website. And that’s exactly what I was about to do. Despite having planned my trip two months earlier, fully knowing I wanted to run this experiment, I had procrastinated until the very last minute to finish my recording device.

I programmed a Raspberry Pi Zero, a computer that costs $5 and is about half the size of a credit card, to connect to my iPhone 12 and take screenshots of the home screen at 1-minute intervals. The program would then check the top right corner of each screenshot and record how many bars I had, which indicates signal strength, and which network I was connected to, such as 4G or 5G. It would then save those metrics along with my phone’s location and the current time while I drove, and at the end of my trip, I’d have a database with thousands of these entries recorded from along my route.

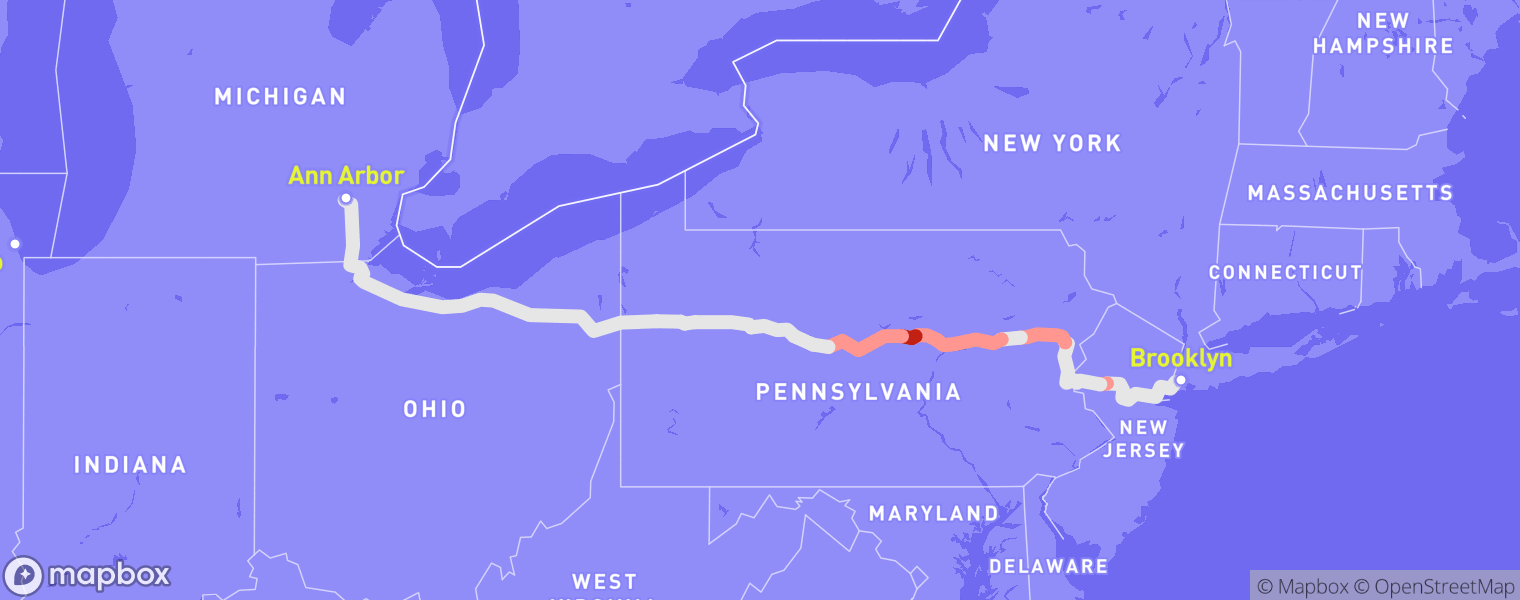

After buying a missing cable and fixing some last-minute bugs, I finally got the device working and pulled out of the parking lot. My first stop was going to be Ann Arbor, Michigan. I was going to drive nine hours from New York City to Ann Arbor in one day, and I was starting at 1pm. One of my many great ideas.

What I didn’t know yet was that I was driving straight into a winter storm. As I started driving along I-80 through central Pennsylvania, the clouds darkened until I eventually saw my first few snowflakes. Within minutes, the flurries had turned into a full-on blizzard. Everyone driving on the highway slowed down from 80 miles per hour, 10 above the posted speed limit of 70, to 40 miles per hour or less. I passed multiple cars that had spun off the highway, and I even placed a 911 call about one that had skidded into a ditch several feet off the road. Visibility was extremely poor.

Several hours later, I finally arrived in Ann Arbor at 12:49am. The drive, which would usually take nine hours without traffic, ended up taking twelve hours. And yet, in my state of exhaustion, I couldn’t help but take a quick look at the data I had collected. Were the T-Mobile coverage maps accurate after all? Did my device even work?

To my delight, the device worked flawlessly. I could clearly see the 575 GPS points lining my route from Brooklyn to Ann Arbor. And the data yielded several interesting insights when compared to T-Mobile’s advertised coverage, which I collected by reverse-engineering the T-Mobile coverage map. On I-80 in eastern Pennsylvania, my experienced coverage was clearly worse than what T-Mobile had advertised. Despite T-Mobile asserting that 5G service was available along my entire route, I could only access 4G for several hours of my drive.

While this alone was an interesting insight, all I could really say at this point was that T-Mobile’s coverage is worse than advertised… in eastern Pennsylvania. To build a strong case about the validity of their coverage map as a whole, I knew I would need much more data. I was excited to spend the next two days with a friend of mine who lived in Ann Arbor, but I also looked forward to the rest of my trip.

‘Limited’ signal strength?

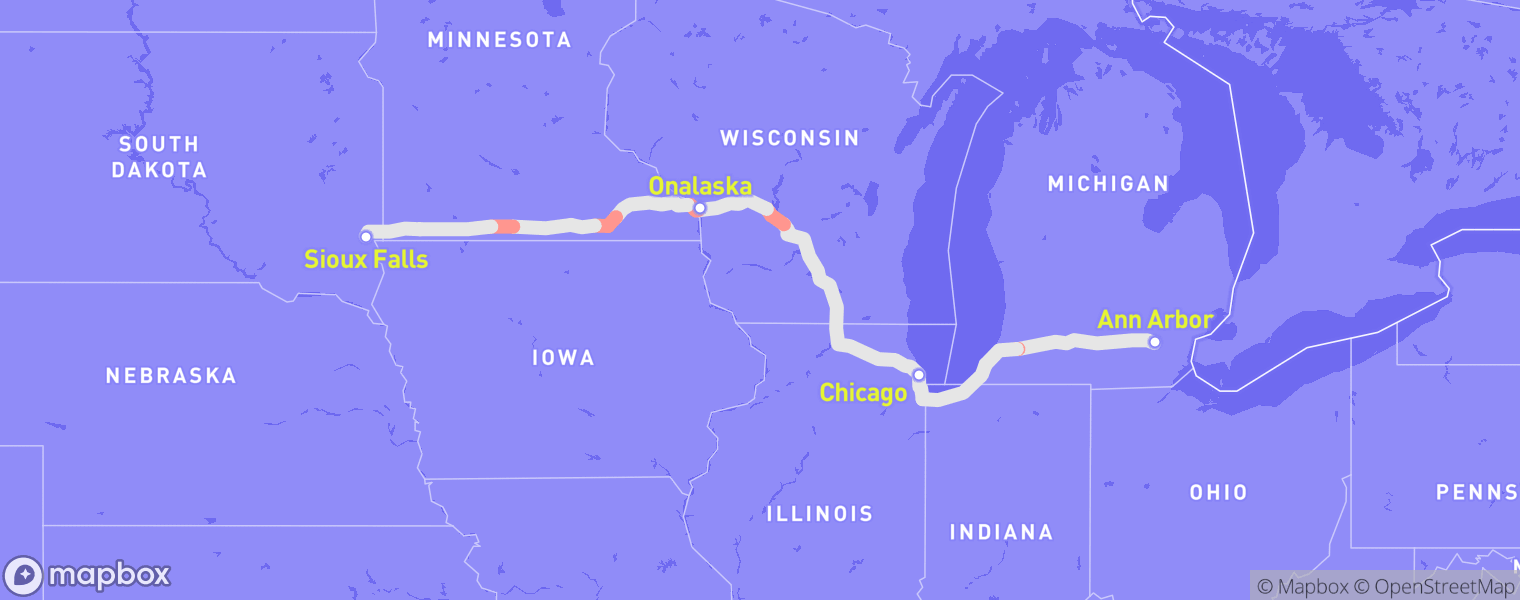

Three days later, I continued my journey. I was in for another long day of driving, from Ann Arbor, Michigan to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. The drive typically takes 12 hours without traffic, and this time, there was no snow in the forecast. Around 9am, I left for Chicago, where I planned to take a routine Covid test. After I finally found a parking spot in Chicago near the CVS where I would take my test, I opened my car door and stepped outside. I still remember what I felt in that moment. Cold. It was freezing. The “Windy City” brought powerful gusts that I could feel in every bone of my body. I put on my coat, stepped into the CVS to take my Covid test, went back to my car, and kept driving.

About four hours outside of Chicago, I got hungry and stopped for a bite to eat. I was in Wisconsin, and according to a friend of mine, driving through Wisconsin meant I would have to try Culver’s. I had never heard of it, but apparently Culver’s is a midwestern fast food chain known for “ButterBurgers,” frozen custard, and cheese curds. After picking up my food at a drive thru, I parked and decided to watch a YouTube video while I ate. I tapped on a thumbnail, watched about five seconds of the video, and… it buffered. I tried turning my cellular data off and on again and reducing the video’s quality to the lowest available setting. It refused to play.

And yet, a quick look at T-Mobile’s coverage map would later reveal that their service in Onalaska, Wisconsin is advertised as 5G. Although, it came with a disclaimer: “Limited signal strength.” Presumably not quite as good as the “excellent” or “good” signal strength indicators it advertised elsewhere, but nowhere on the page did it explain what this meant. How much better is “good” than “limited”? “Excellent” compared to “good”? Should I expect to be able to watch a YouTube video if my coverage is “limited”? Stream a song on Spotify? How would this factor into my decision to buy a T-Mobile plan?

While writing this story, I found that as of December 2021, T-Mobile has removed these qualifiers from their coverage map, perhaps because of this ambiguity. Today, the coverage map in Onalaska just depicts 5G service as being available, with no indication of speed or reliability, which likely helps T-Mobile paint a rosy picture of their service to potential customers. Customers have no way to tell whether the 5G service they’re purchasing is going to be fast and reliable, or slow and spotty. Although having a limited understanding of service quality was better than nothing, this is arguably worse. It makes me wonder why there aren’t more stringent regulations on the coverage maps published by carriers.

I finished my ButterBurger and got back on I-90. The burger and fries were delicious, but I wasn’t sure when I would get the chance to try them again. I wondered why Culver’s hasn’t expanded beyond the Midwest. I kept driving, and about four hours later, I arrived in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I filled my gas tank for the third time that day, checked into my Airbnb, and quickly checked my results again before getting some rest.

Surprisingly enough, I found that T-Mobile’s service was almost exactly as advertised for the entire 12-hour drive. The coverage map showed that parts of Michigan only had 4G, with 5G available along the rest of my route, which matched my recorded data. Would my final conclusion be that T-Mobile’s coverage map was actually… accurate? Only time would tell.

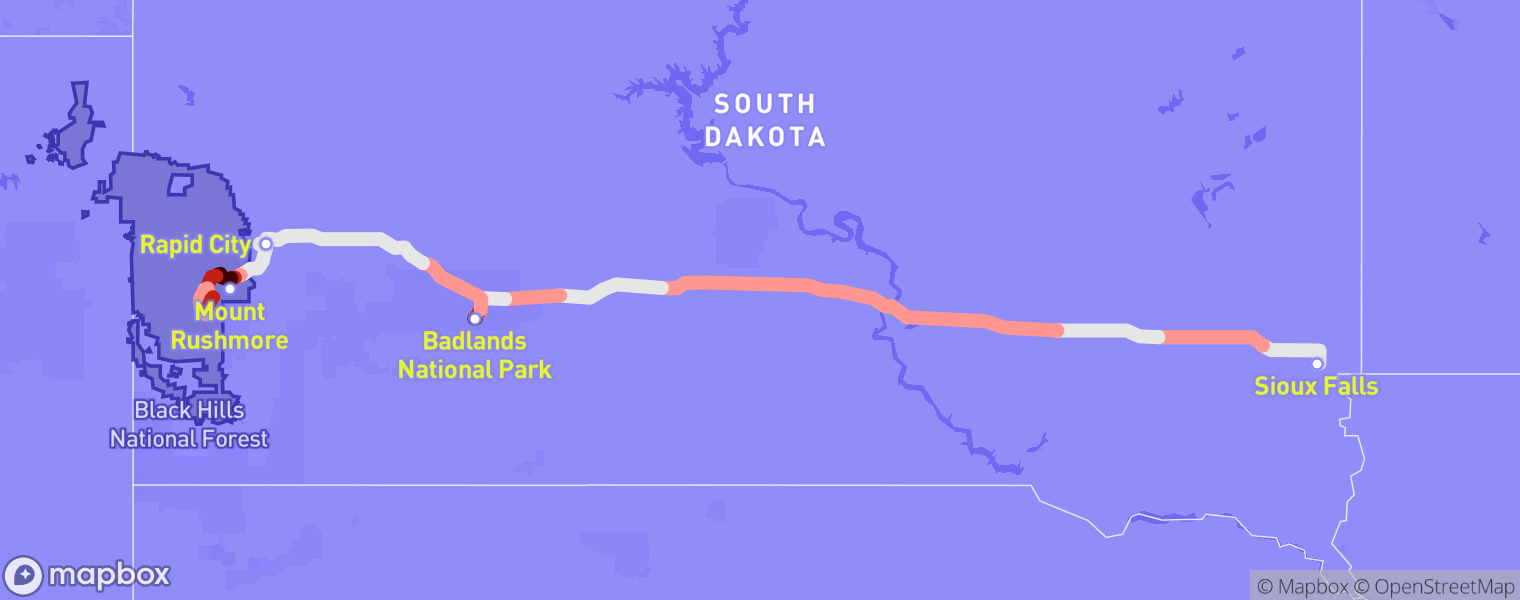

I woke up the next day and decided to check out Sioux Falls, since I wasn’t sure if I would ever be back. I pulled out of the driveway and found myself behind a car with a bumper sticker that read, “Minnesota Sucks!” I drove around for a few minutes, passing by sights such as Falls Park and St. Joseph Cathedral, before beginning my five-hour drive to Rapid City, the second largest city in South Dakota. I wasn’t too sure what I should have expected, but the drive, which went entirely along I-90, was almost completely empty. Miles upon miles of nothing, as far as the eye could see.

However, there’s plenty to do in South Dakota once you get near the western side of the state. I stayed in Rapid City for three days, during which I made sure to visit Badlands National Park and Mount Rushmore. I also hiked Black Elk Peak, the tallest mountain in South Dakota.

At the end of my time in Rapid City, I compiled my results from South Dakota. I was especially curious to see my results from Black Hills National Forest, home to Mount Rushmore and Black Elk Peak. My recordings made on that day were some of the first I hade made off of major highways, and I didn’t have any cell service at all for portions of my time there.

Sure enough, T-Mobile advertised that they covered every location within the Black Hills that I had driven through. And yet, I only had service at 63% of all locations I had recorded from within the forest’s boundaries. I wasn’t able to record data outside of my car, but given how different these results were compared to my recordings made on interstates, I wondered if the results would have deviated further if I could have additionally taken recordings from hiking trails.

Spotty signals

Two days later, I left Rapid City and started the next chapter of my trip. I was leaving the midwest and entering the northwestern United States. Despite some inconsistencies in Pennsylvania and South Dakota, my cell signal had mostly matched what T-Mobile had advertised, likely due to the abundance of flat terrain. Cell service is transmitted through radio waves, which easily pass through air but can be blocked by hills and mountains, making flatter states such as Wisconsin and Minnesota perfect for receiving a good signal.

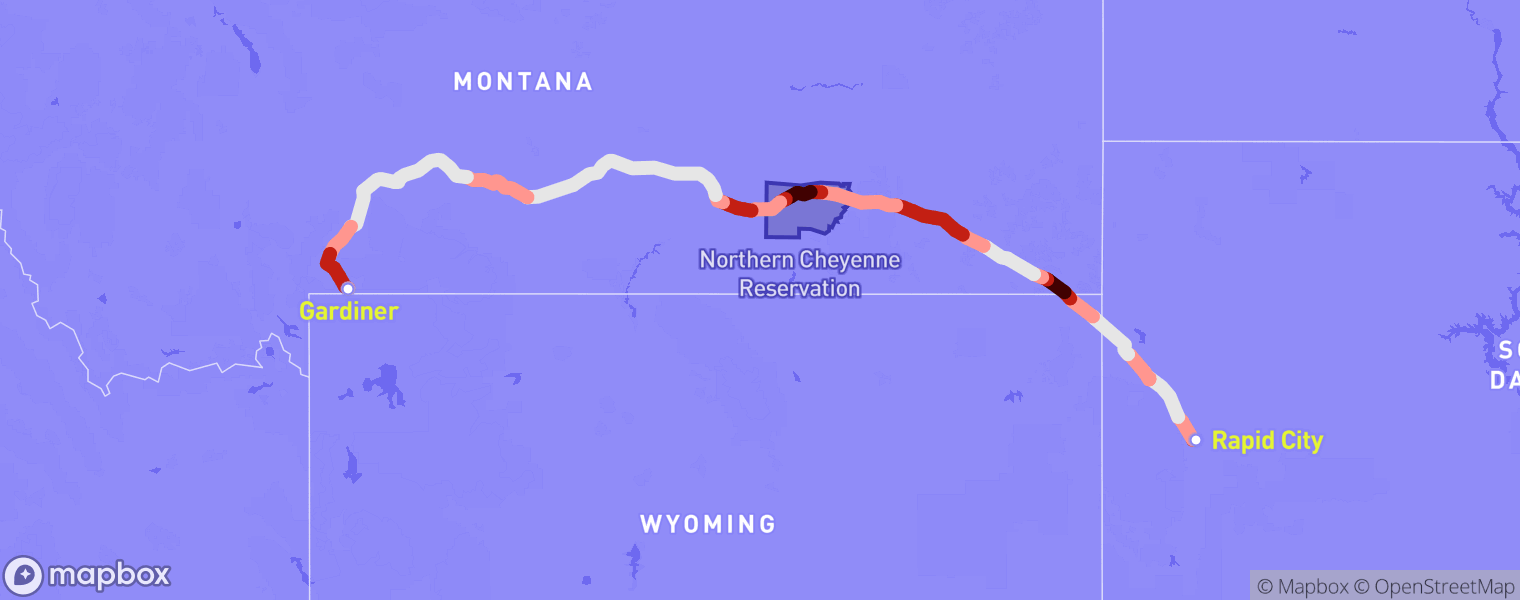

I had also been driving mostly along interstates, which I suspected to be places that cell providers paid extra attention to when setting up service for an area. My next destination was Gardiner, Montana, a small town seated at the northern entrance to Yellowstone National Park. To get there, I would need to drive along some state highways for several hours before eventually rejoining I-90 later in the day.

The first few hours I spent on state highways in South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana were brutal. These highways featured lots of packed snow and black ice, and they were also one-lane highways, which made it much more difficult to overtake the large, slow semi trucks.

However, the last hour I spent before merging back onto I-90 went through the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, which featured one of the most beautiful drives of my entire trip. A heavy snowstorm had passed through the region the day before, coating all of the evergreen trees in a thick layer of snow and giving it the appearance of a winter wonderland. I didn’t have time to make a stop, but I made a mental note to come back someday in the future.

I then spent two and a half more hours on I-90 through Montana before turning onto U.S. Highway 89, which was also phenomenal. The drive to Gardiner passes through Paradise Valley, which must get its name because it looks like paradise. I drove between sets of enormous snowcapped mountains while watching the sun set over the peaks on my right. I also got to admire the Yellowstone River and the beautiful rolling hills. It’s common to see wildlife along this highway, but I unfortunately wouldn’t see any until I got to explore Yellowstone later in the week. I finally checked into my Airbnb around 6pm. This was the first location on my roadtrip where I would stay for more than a couple days, so I took some time to buy groceries, unpack, and cook dinner before checking my results.

As I had expected, results from the day’s drive were noticeably worse than what I had collected in the Northeast and the Midwest. For several minutes along a state highway in southeastern Montana, and again while passing through the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, I had no signal, despite T-Mobile’s claims that both areas were covered with 3G service or better. I also observed that data collected along I-90 matched T-Mobile’s advertised coverage much better.

Based on the results of my first major drive along non-interstate highways, it appeared to me that T-Mobile may be exaggerating its coverage even further for rural and underserved areas. I would have to wait to confirm this hunch by running this analysis again at the end of my trip.

I then spent a week snowshoeing in Yellowstone, which I can’t recommend enough. Most people choose to visit Yellowstone in the summer months, but there’s definitely something to be said about the beautiful winter scenery. Although cell service is spotty in Yellowstone, this was the one part of the country where I didn’t really mind having poor reception.

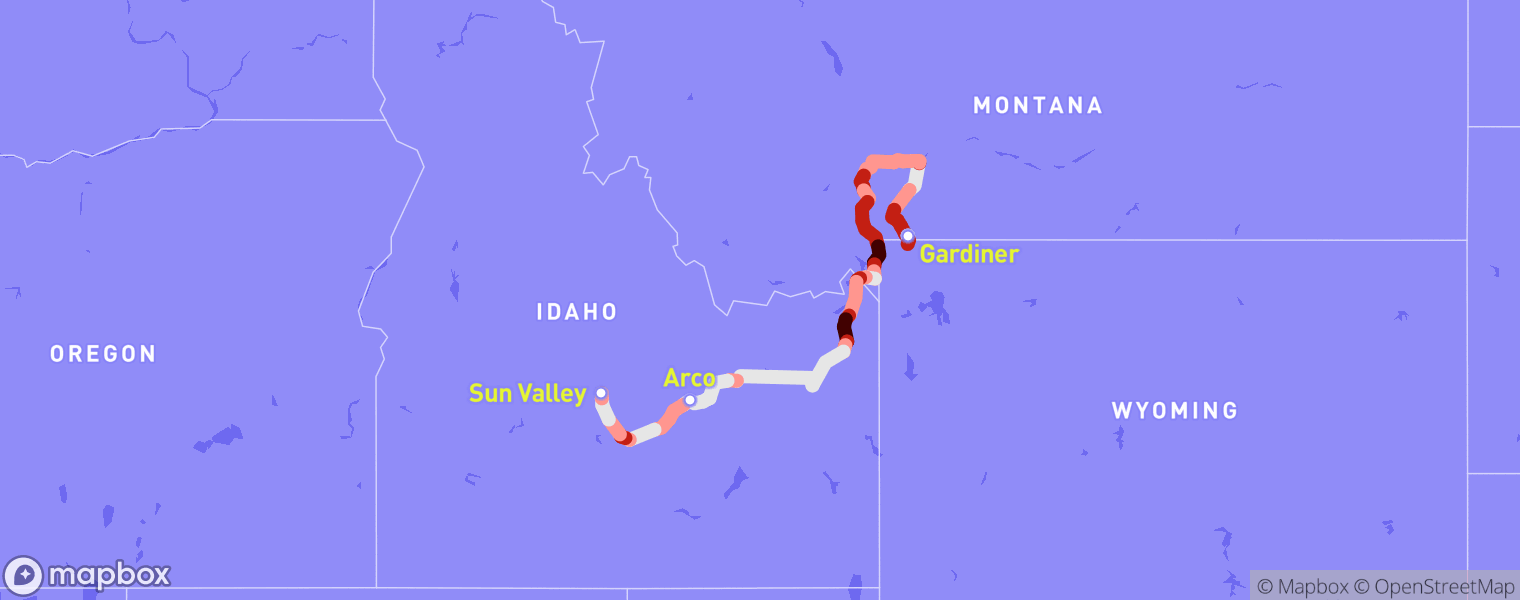

A week later, I finally said goodbye to Yellowstone. I then drove about 4 hours to Idaho Falls, Idaho, to take another routine Covid test, before continuing for another 3 hours to Sun Valley, Idaho, where I would ski with my dad and sister, who were joining me for the next week and a half. The drive went mostly along state highways again, which I was growing a liking to. Despite having little to no cell service for most of the drives, the scenery was much more interesting than what I had been observing from interstates.

As a result, I got to pass through towns like Arco, Idaho, the world’s first community to be lit entirely by nuclear power. I learned that the state of Idaho is almost entirely flat, with the notable exceptions of the Rocky Mountains and the Menan Buttes. The buttes are two of the world’s largest volcanic tuff cones, which are essentially large rocks formed in the aftermath of a volcanic eruption. Despite their massive size, rising about 800 feet above the plains below, they only formed about 10,000 years ago, more recently than the first human migration into North America.

Some time later, I arrived in Sun Valley. As I was driving through the town, something felt off, but I couldn’t put my finger on what it was. And then it hit me: the street I was driving on had a bike lane. I hadn’t seen a bike lane since I was in Chicago, 2 weeks and 2,000 miles ago. I faintly recalled reading something about how, in the United States, the presence of bike lanes tends to correlate with how likely a town is to vote Democrat. I wondered if that would hold true for Sun Valley, considering Idaho’s status as a solidly red state.

Once I got to our motel, I looked it up, and sure enough, Sun Valley is the only part of Idaho that reliably votes Democrat. I found it interesting to see the correlation hold up in practice. Then, I checked my results.

Once again, the time I spent driving along state highways in Montana and the northeastern corner of Idaho was riddled with service that was worse than what T-Mobile had advertised in that area. After driving further into Idaho, service improved greatly, which is likely due, again, to Idaho’s mostly flat terrain.

We stayed in Sun Valley for the next 9 days. Sun Valley was a ski resort I will never forget, with excellent skiing conditions and a cute resort town. It remains the only place I have ever seen road signs that say, “No hunting within city limits,” which I thought was obvious, and “Sleigh crossing.” Highways surrounding the area often had tracks running alongside them for snowmobiles. The cherry on top was the view from the top of Bald Mountain, Sun Valley’s primary peak, likely the best I have ever seen from a ski mountain.

Lost without signal

A week later, I began my drive to Park City, Utah. I intentionally took a route that was slightly longer in order to avoid interstates and collect data from more remote areas. This turned out to be a blessing and a curse. As had been the case for the past few weeks along state highways, the drive was beautiful. However, as I had seen on my recent drives, the cell signal was much worse.

I eventually stopped for gas in Evanston, Wyoming, population 11,848. The only available network was 3G, likely from a T-Mobile partner, which allowed me to make phone calls and text messages, but prevented me from accessing the Internet. The last time I remembered having a data signal was over an hour ago. After filling up on gas, I continued driving south along my route which avoided major highways. It turns out there are no real highways south of Evanston, so my route went along unpaved, unnamed roads for the majority of the drive from here.

45 minutes outside of Evanston, Google Maps crashed. It had been an hour and a half since I had a signal, and about 35 minutes since I had seen another car. I panicked. I stopped the car to check my phone, and the route was gone. I was stunned. I tried zooming in on the map, seeing if I could piece together some roads that would eventually get me to Park City. No luck. Nothing would load. I was essentially lost in the middle of nowhere. It had been awhile since I had seen a sign indicating a mile marker or a nearby city, and the few signs that did exist were not very helpful. This part of Wyoming wasn’t designed for tourists.

I eventually decided I would continue driving forward. Google Maps led me here, which meant the route to Park City had to be ahead. The roads around here were also very long and mostly straight. I figured if I used my phone’s compass to make turns that took me west, I would eventually find a highway. I hit the gas pedal.

Maintaining about 25 miles per hour along the unmarked, snowed-over dirt road, I continued ahead. I thought there was nothing in South Dakota, but I learned there’s even less in the southwestern corner of Wyoming. About 20 minutes later, I reached an intersection, marked by a sign with a road number that had been riddled with bullets. I decided to take a break and admire the fact that I was likely about as far from civilization as I had ever been. I hadn’t had cell service for two full hours, and it had been an hour since I had even seen another car.

It was very cold, so I didn’t stop for long. I turned west and continued making my best guesses at the turns I should take along Wyoming’s country roads.

About 25 minutes later, I finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel. Another intersection was coming up, but this one was different. The road ahead was paved. I turned west again and drove, hopeful that I would find service soon. Another five minutes passed before I finally spotted another car. A Ford F-150 that used to be a bright shade of red, but was covered in dirt and grime. A symbol of hope. I’m sure my car didn’t look much better.

I started glancing at my phone more frequently, hopeful that I would get a signal soon. About 10 minutes later, it finally came. I had 1 bar of signal, and I was connected to a 4G network. I stopped in the parking lot of a tiny local church and checked my phone. Where was I? Coalville, Utah. The service was painfully slow, but it was present, and that was all that mattered. I typed in my destination in Park City and loaded the route, with Google Maps’s “avoid highways” feature turned off. I was done with the adventure, at least for now. Around 10pm, I checked into my Airbnb and crashed. I was exhausted.

The next morning, I woke up and brought my belongings inside. I had held onto several cooking supplies from the past few weeks, and to my surprise, the olive oil I had left in my car had frozen completely. I didn’t even know that was possible. The weather that morning had been in the single digits.

Once I was settled in, I opened my laptop and looked at my results from the previous day. If T-Mobile claimed I should have had reception along any part of the desolate 2.5-hour stretch of the previous day’s drive without cell service, I was ready to lose all hope in their coverage maps.

As I had mostly expected by that point, T-Mobile advertised stellar coverage in the middle of nowhere. Most of the time I was lost, I had been in Uinta County, Wyoming, and Rich County, Utah, shaded in gold on the map above. In these two counties, T-Mobile advertised 4G and 5G service for the bulk of my drive, which went along Utah’s Highway 16, Wyoming’s Highway 89, and various unnamed country roads. However, my phone had either 3G or no service in every recording made within these two counties. Even when my phone did have 3G, it couldn’t connect to the Internet, which had prevented me from loading Google Maps.

According to T-Mobile’s map, I should have had Internet access through either a 4G or 5G connection for 72% of the time I was in these counties, and I should have had “Partner: 3G / 2G” coverage for about 13% of the time I was in Rich and Uinta counties. Instead, I experienced 3G coverage without data 75% of the time I was there, and no service for the remaining 25%.

To add insult to injury, T-Mobile doesn’t provide many details about what the “Partner: 3G / 2G” level of coverage even entails. In these areas, the map comes with a disclaimer: “Coverage is provided by partners in these areas, so speeds and connections may vary.” Even if I had looked at the coverage map in advance of my trip, I had no way to know in advance that this specific variety of partnered coverage came with calls and texts, but no data connection. Oh well.

Park City featured, without a doubt, the best skiing conditions I have ever seen. Shortly after I arrived, a major snowstorm hit the region, dumping over a foot of fresh snow on the slopes. My Airbnb lost power, but the ski slopes were open. I was ready.

I originally planned to stay in Park City for one week, but after a few days of skiing, the conditions were so good that I decided to extend my reservation for another week. I’m sure it’ll be awhile before I find conditions that come even close.

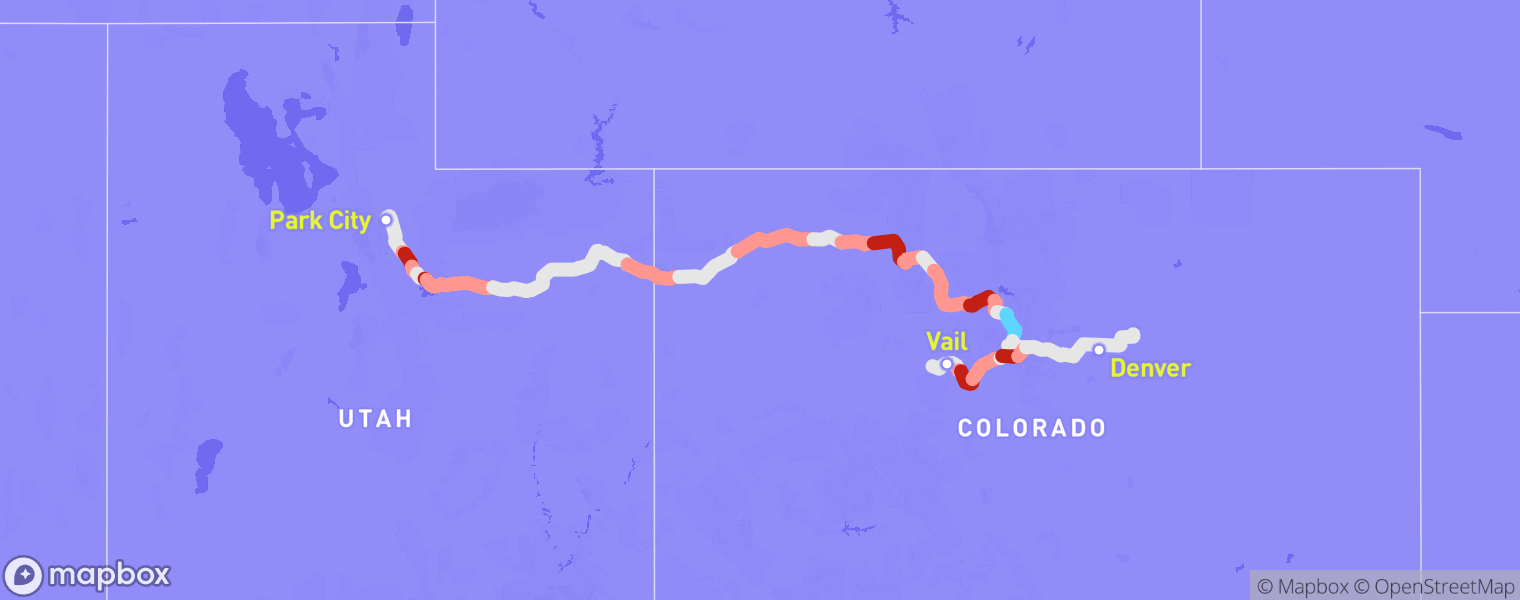

My next and final stop was Vail, Colorado. I planned to pick up two friends from Denver International Airport and then drive two hours back to Vail, where we would stay for a week and a half. I chose to avoid interstates again for part of the way to Denver, which once again did not disappoint. Fortunately, this route stuck to paved state highways instead of middle-of-nowhere dirt roads. However, even the parts of the drive that did go along major highways were incredible. I-70 from Vail to Denver goes through a valley that offers spectacular views during the day.

Once again, my experienced coverage was worse than advertised for most of the drive. However, for half an hour before merging onto I-70 to Denver, I actually experienced coverage that was better than advertised: 4G service was advertised in this entire region, highlighted in blue on the map above, but I had 5G service almost the entire time. This would remain the only time where my coverage was better than advertised for more than a couple minutes during the entire roadtrip.

It was great to ski with friends again after spending two weeks in Park City on my own, and once again, the conditions were great. Before this roadtrip, I had never skied in the Rockies. Sun Valley, Park City, and Vail absolutely did not disappoint.

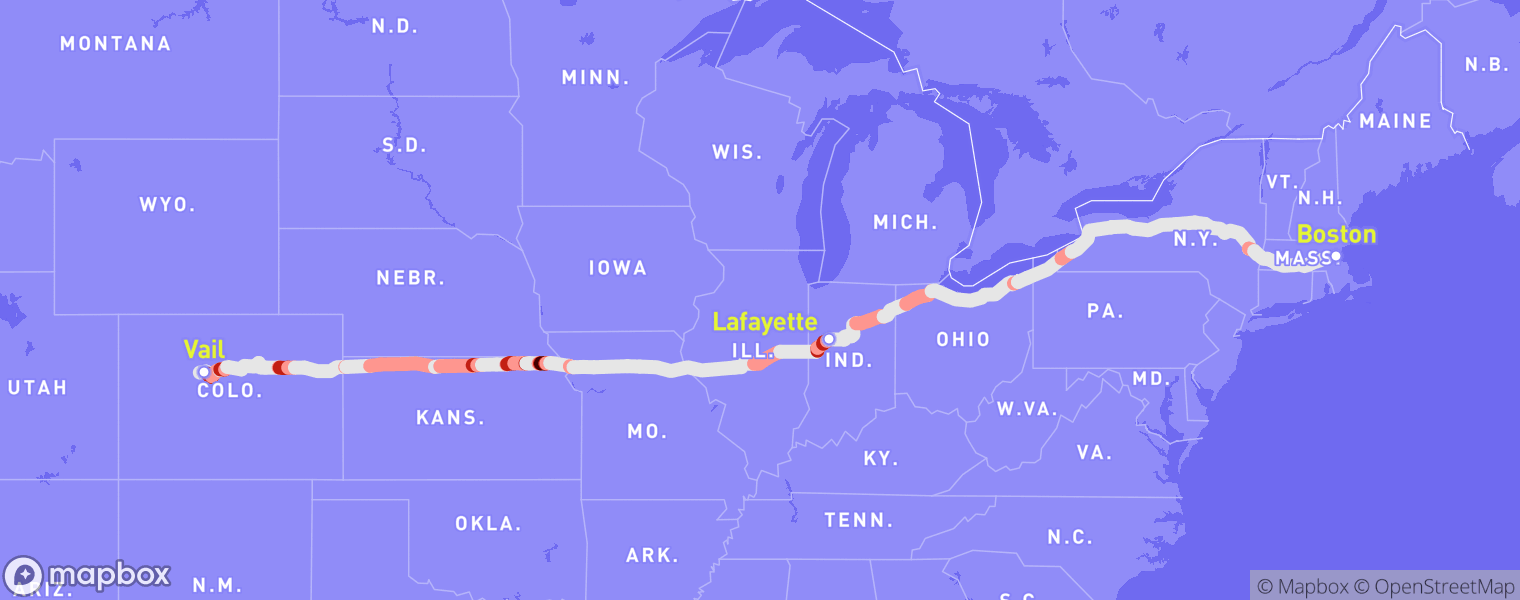

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end. All three of us are MIT students, and our spring semester was set to begin on February 16, which eventually meant it was time to go. One of my friends, Julia, chose to accompany me on the drive home, which we decided we wanted to complete in 2 days. Despite the shortest route from Vail to Boston taking 30 hours to drive, Julia agreed to my plan to route along state highways for most of the drive, which would increase our trip’s duration to 36 hours. In 2 days. She, too, was a dissatisfied T-Mobile customer.

Leaving Vail meant the end of enjoying beautiful views along state highways. Shortly after dropping our other friend off at Denver’s airport, we crossed the border from Colorado into Kansas, which quickly became my least favorite state. It felt like it never ended. Rolling hills as far as the eye could see in every direction, with nothing but farmland surrounding us. The only notable feature I remember from this part of the trip was when we passed a sign marking the Geographic Center of the United States. After what felt like an eternity, we checked into our Airbnb in Lafayette, Indiana around 3am. At 19 hours, it was the longest I had ever driven in one day.

We woke up around 10am and set off for the last time. I got another routine Covid test at a Walgreens in Kokomo, Indiana, and then we navigated along the shortest route to Boston. After such a long drive the day before, neither of us was in the mood to prolong our journey.

Finding activities to pass the time proved difficult, as the day before had already exhausted all of the songs we wanted to listen to and roadtrip games we could come up with. We decided to listen to Jerry Seinfeld’s audiobook, “Is This Anything?,” a six-hour collection of one-liners and whimsical anecdotes that comprise the best material he had come up with over his entire career. Seinfeld is good, but it also got old quickly. We didn’t have much else to do. We eventually crossed the border into New York, and then into Massachusetts, before finally arriving in Boston at 3am, 17 hours after we departed from our Airbnb. I had been behind the wheel for 36 of the past 43 hours. I was ready to leave my car parked for the next month.

And yet, in my state of exhaustion, I was filled with a feeling of awe at the vastness of the country I had spent my life in. For all of the 21 years I have been alive, I have lived in New York City and Boston. I’ve visited some other major cities around the United States, but just six weeks earlier, I had never been on a roadtrip. The trip gave me an excuse to visit so many new and interesting places, but I had still skipped a majority of the country, making basically no stops on my way back from Vail, or even touching the western or southern parts of the country. I promised myself I’d go on another crazy roadtrip someday.

But let’s not get distracted: the real fruits of my labor were finally ready to harvest. I now had 7,000 miles of data that I could finally use to answer the question that started it all: Does the T-Mobile coverage map depict real-world data? Or are they openly lying to unsuspecting potential customers? I checked the results of my drive back from Vail before diving into the data.

The results were pretty similar to what I had previously seen in the Midwest. Despite exceptions in a few locations, they largely matched T-Mobile’s advertisements, which can again likely be attributed to the flat terrain west of the Rockies. Now that I’ve processed all my driving results, we can look at a deeper analysis.

Results

The first question I wanted to answer was simple: on average, does T-Mobile exaggerate its coverage? Considering I had only found one region, in Colorado, where my coverage was better than advertised, I already had a hunch about what the answer would be.

We can see above that my service was worse than advertised 33% of the time. My service was also better than advertised 3% of the time—most of these instances were one-off and didn’t appear on the maps because they would only happen for a brief moment. However, when my coverage was worse than advertised, it would often persist for at least several minutes.

I also wanted to follow up on my earlier analysis of service on interstates versus other highways by performing the same analysis for my entire roadtrip.

As I had expected, T-Mobile’s claims hold less water when you leave interstate highways. It’s important to note that it’s not just that the quality of service is worse off of interstates, which should be expected, but that T-Mobile’s claims are more exaggerated off of interstates. In other words, people who live in more remote parts of the country are more likely to be deceived by T-Mobile’s coverage map. Not good.

The last question I wanted to answer was about T-Mobile’s claims of nationwide 5G. T-Mobile has, for years, claimed they are a leader in 5G coverage. Their homepage currently claims they have “more 5G bars in more places,” and they claim to have deployed the first nationwide 5G network.

However, their advertised service quality exceeds what I should have observed on my roadtrip. Despite advertising that I should have received a 5G signal 77% of the time, I only observed 5G 52% of the time. Most of the time, this was replaced with a 4G signal, but occasionally I had either a 3G signal or no service in these areas as well.

With these results, I had essentially confirmed the suspicions I had all along. Not only is T-Mobile’s map misleading in general, but it is also more misleading in more remote locations. This hurts me as a customer who enjoys hiking and skiing, often in remote, mountainous regions of the country, who wants to make sure I’ll have service when making plans. It also hurts the people who live in these more remote areas, who are more likely to rely on a cell signal as their primary Internet connection.

To make sense of these results, I called Corey Chase, a telecommunications infrastructure specialist with Vermont’s Department of Public Service who made headlines in 2019 when he spent six weeks driving all over Vermont to prove coverage maps were misleading within the state.

I started the interview with one question: “AT&T identifies cost as one of the major roadblocks to collecting more coverage data. Do you believe this is accurate?”

This would turn out to be the only question I needed to ask: for the next 15 minutes, Chase explained everything I would have wanted to know about coverage data. “Every major cell phone company does drive tests of every major road every 6 months.” He continued, “They know exactly what service is where. They don’t want to talk about this.”

As it turned out, his project was powered largely by volunteers, who were happy to drive circles around Vermont if it might eventually improve their cell signal. In total, Chase said it took about 6 weeks and $3-5k to record cell phone data from all of Vermont’s major roads and many of the state’s less-traveled roads. Almost all of the money was spent buying new phones used to collect the coverage data. Chase speculated that with used phones, the project would have cost just $600, spent on a web server to store the results and the coverage plans from each major carrier. He added, “It’s ridiculous that anyone would say it’s too expensive to do this.”

During the interview, I was shocked to learn about the routine data collection done by carriers. If these data were fed back into the carriers’ coverage maps, I should have observed results that were much more in line with what T-Mobile publishes on their website. When asked to respond to the findings presented in this story, Armando Diaz, a spokesperson for T-Mobile, wrote back, “We stand by the accuracy of our maps,” without elaborating or addressing my results further.

I was also shocked by Chase’s kindness throughout the interview, and his willingness to talk to me, someone who is not a journalist, doesn’t even live in Vermont, and was mostly doing this project to satisfy my own curiosities. At the end of our chat, I made sure to thank him for his time, to which he replied, “Of course. Anything we can do to get better coverage.”

I would like to thank my friends and family who offered feedback on this year-long project. I would additionally like to thank Julia for driving from Vail to Boston and helping me collect more data instead of flying home from Denver. And of course, I would like to thank Professor Jared Berezin for his advice throughout the writing process.