Organizing the first virtual HackMIT

Cambridge, MA — October 20, 2020

I just want to preface this blogpost by acknowledging that I would not be where I am today if it weren’t for collegiate hackathons. Despite declining hackathon sponsorship over the last several years, I think it is paramount that tech companies and universities continue to support these events.

My first hackathon was Hack the North, back in 2014. I built Droidboard, a Python script that converted iOS storyboard files into functioning Android apps. No sponsor was interested in recruiting a high school freshman, but I remember being blown away by the people I met, the mentorship I received, and the swag and food I enjoyed throughout the weekend. In fact, I was so hooked by Hack the North that I attended 21 other collegiate hackathons in the 2014-2015 season, and I’m still in touch with the friends I made at Hack the North and several other hackathons I attended over six years ago. Through repeatedly building small projects at weekend-long hackathons, I eventually went on to win second place at Hack Gen Y, third place at McHacks 2015, and first place at HackNY Spring 2016.

Without these hackathons, I would not have made the lasting connections or learned the skills necessary to succeed in the computer science industry, which is why it is so important that these events continue to thrive. My overwhelmingly positive experience drove me to want to share hackathons with my peers, because I think these events should be readily accessible to anyone who is interested in computer science. I started my own hackathon in high school, and luckily, for the past two years, I’ve had the pleasure of being part of the HackMIT organizing team.

The first year and a half of my time on the team was super exciting, and also mostly what I had expected. I made a bunch of new friends, I helped organize Blueprint 2019, HackMIT 2019, and Blueprint 2020, and I became a co-director in the spring of my freshman year. I helped put together an awesome line-up of speakers, reimbursed the travel of the hundreds of hackers who traveled to Boston, and did a bunch of other things along the way.

You probably know what’s coming next.

Around the beginning of March, everyone started discussing this virus that was spreading through China and Italy. We didn’t know it yet, but literally everything was about to change. To the best of my memory, here’s a timeline of how we realized a physical HackMIT was not going to happen in 2020. If you already know the whole story, feel free to skip to the bottom.

- (Feb. 9) We finish organizing Blueprint 2020

- (Feb. 16) I attend TreeHacks with a few other HackMIT organizers. Palo Alto was a nice warm escape from the Boston winter. Life at this point is still extremely normal.

- (Mar. 5) Two significant events take place:

- Three Biogen employees test positive for COVID-19 following a 175-person meeting in Boston [source]. This was probably one of the first reports of cases in Boston, at least as far as I can remember.

- That same evening, MIT sends the first of many emails to the student body. Among other things, it says, “Effective immediately, if you are planning any in-person MIT event with more than 150 attendees, […] you must postpone, cancel, or ‘virtualize’ it.” [source]

- I realize we were very lucky to have chosen a weekend in February for Blueprint, and not a weekend in March. I bet TreeHacks was also glad their event took place in mid-February.

- Everyone slowly realizes that CPW, the weekend in which we invite the accepted students to campus, would be cancelled. Ring delivery, senior prom, graduation, and other usual events aren’t looking so great either.

- (Mar. 8) We wrap up spring recruitment for HackMIT, as we would in any other year. Everyone is talking about the virus, but it still feels a little distant.

- (Mar. 9) We have our first HackMIT general meeting with our new team members. We didn’t know this yet, but this would be our last in-person team meeting for a very long time. It remains the only time that many of our newest team members have ever met the rest of us in person.

- (Mar. 10) This was probably the craziest day of them all:

- (8:25am) I receive a long and scary email from Harvard (I was cross-registered last semester). It says that all classes will be instructed virtually starting on March 23, and that students would not be returning to campus after spring break, which was next week for Harvard. [source]

- (8:45am) I bike over to Harvard to take my Harvard class. By the I got to the classroom, everyone had seen the email, and everyone was talking about it. Multiple people who were traveling abroad for spring break didn’t know whether or not to cancel their plans. I have literally no idea what we learned that day.

- (some time later in the morning) Screenshots of notes of conversations various students were having with MIT’s administration begin circulating among MIT students. Rumors and gossip spread for the entire day. Nobody is getting work done, and nobody knows what’s going on.

A message sent by a previous HackMIT organizer in our Slack workspace. - (5:02pm) MIT finishes composing their email and sends it to everyone. Classes are cancelled for the week of Mar. 16-20, and students must leave campus by March 17. [source]

- Everyone is pretty shell-shocked. People start saying goodbye and figuring out where to store their things. Seniors realize the next few days may be their last time seeing many of their classmates.

- (Mar. 11) Zidane Abubakar, a former MIT student, snaps a photo of students gathering at Killian Court, with one person holding one of the hand sanitizer stations that had appeared all over campus a few days earlier. The photo becomes iconic.

- (Mar. 12) Goodbyes continue. At 10:45pm, MIT announces that they will reimburse an additional $500 per student to change travel reservations such that they can leave campus by Sunday, March 15. [source]

- (Mar. 13) I finish packing up all of my things and leave campus late at night. I had originally planned to leave on March 16.

- (Mar. 15) MIT announces that all classes will adopt a pass/no record grading policy, meaning that letter grades will not appear on your transcript. [source]

- Classes don’t continue until March 30. Everyone spends the extended spring break quarantining at home, nervously watching COVID-19 counts rise, and comprehending what had just happened.

- (Apr. 27) It becomes clear that the pandemic is not improving in the U.S. at the same rate it is improving in other countries. We make the call to plan for a fully virtual HackMIT.

When I started writing that timeline, I honestly didn’t expect it to get as long as it did (sorry!). Thinking back on it, I can’t believe how quickly things changed. On March 4, everything was basically normal. On March 5, there were a couple COVID-19 cases in Boston, and large events were cancelled, but everything was still pretty normal. Just five days later, we were told to leave campus as soon as possible. Isn’t it crazy that face masks didn’t even become commonplace until later in April? And now, 7 months later, we have a slightly better understanding of how the virus spreads and what its effects are, but the pandemic still presents an enormous issue across the country. I feel that I’m making the best of our time apart, but everything has become more difficult, and I have no idea when I should expect things to return to normal.

HackMIT goes virtual

Anyway, back to HackMIT. On March 5, one of our former team members, Gonzo, wrote the following Facebook post:

This was the same day we received the email from MIT about large events being cancelled, when everyone collectively realized that CPW (campus preview weekend) would be rendered impossible. A few days later, I realized that if HackMIT had to go virtual as well, this proposed “Club Penguin” approach could probably work for us as well. I knew that I probably had the skills needed to build this thing, and I knew that it would probably be the best way for us to enjoy the virtual format. Gonzo deserves full credit for planting this seed in my head.

Two months later, on April 27, we made the call to plan for a virtual HackMIT. I knew I wanted to build this platform, which would affectionately become known as “Hack Penguin.” However, there were a couple problems that I didn’t really see coming: our upcoming virtual event had basically no precedent, and I had no idea how to lead a big project.

Let’s focus on the first problem for a second. By the time we made the call to go virtual, we realized that some parts of our event would stay mostly the same, and some parts of the event would have to change dramatically. For example, in a virtual hackathon, there is no food, there are no travel reimbursements, and there are no venues to reserve. Soon enough, there will be nobody on our team who has done these things before, but that’s a separate problem. Some of the tasks that are kept in a virtual format include speakers, scheduled mini-events, sponsors, and prizes. I was on point for speakers, and this becomes a significantly easier task when you don’t need to convince your speakers to travel to Boston. We had an incredible line-up this year, featuring the founders of companies such as Duolingo, GitHub, and 23andMe.

Prizes is a good example of a task that stays roughly the same. In a virtual format, we still need to mail things out to our winners. Sponsorship is a good example of a task that becomes significantly more difficult. Many of our previous sponsors were quickly losing revenue as consumer spending plummeted during the pandemic, and this led to many companies cutting back on recruiting or eliminating hackathon sponsorship from their budgets entirely. Companies such as Airbnb, Uber, and Boeing still have a long and uncertain road to recovery ahead. As we got closer to the summer, websites such as ismyinternshipcancelled.com popped up to track which companies had cancelled their summer internship programs, which likely meant they wouldn’t be recruiting this fall. It also became more difficult to convince companies that hackathon sponsorship was still worthwhile when they couldn’t interact with our hackers in person.

When we looked at these challenges, we naturally wondered if anyone had solved these problems before. Unfortunately, there wasn’t really anything that we could compare our situation to. Some hackathons, such as LAHacks (UCLA) and HooHacks (UVA), had to quickly move to a virtual format in the spring, but they didn’t have several months to plan this transition like we did. Other hackathons, such as hack:now (UC Berkeley) and the MLH Summer League were always intended to be virtual events, but these weren’t great parallels either, because anyone could sign up and participate in these events, whereas we decided early on that we wanted to keep our admissions process to ensure we could provide everyone with judges, mentorship, and swag. This all meant that we didn’t have a lot of precedent. We were probably going to become the one of the first major virtual collegiate hackathons that had several months to prepare their event.

The second problem of project management was also a little tricky. I was now HackMIT’s older co-director, and I was excited about starting the Hack Penguin project, but it turned out I had no idea how to do this. I’m decidedly not a natural leader, and while organizing HackMIT 2019, I relied on my older co-director, Jessica Sun, and my logistics director, Kye Burchard, a lot more than I originally realized. They filled in the communication gaps and random things I had missed in the planning process, and ensured that everything went smoothly on the day of our event. In my mind, I could clearly envision the end goal of this platform: a place where hackers could walk around, talk to each other, talk to our sponsors, and explore. However, I knew I wouldn’t be able to do this alone, and I originally struggled with communicating all of this to our team. I spent a large chunk of the summer organizing meetings to discuss various aspects of the platform and getting better at dividing the work that needed to be done into tasks that I could assign out to members of our team. Over the summer, I could feel myself getting better at project management, and I’m very happy with how things ended up. But I definitely struggled with this a lot.

Hack Penguin comes to life

We decided that we had two major goals with Hack Penguin. First, we wanted to provide a unique way for everyone to stay connected while we were all apart. Second, as (probably) one of the first events of our kind, we wanted to build something that was unique and memorable, in a way that would make our event stand out. We devoted a lot of time and effort into the platform, and put a ton of thought into each feature that went into it.

On May 25, I finished up the first (very rough) working demo of Hack Penguin. Two computers could connect to a shared backend server, and watch each other walk around the screen. That’s all that you need for a hackathon, right?

The project progressively picked up speed over the summer. Here’s a video from mid-August:

Here’s one from late August:

Here’s one from just a few days before our event:

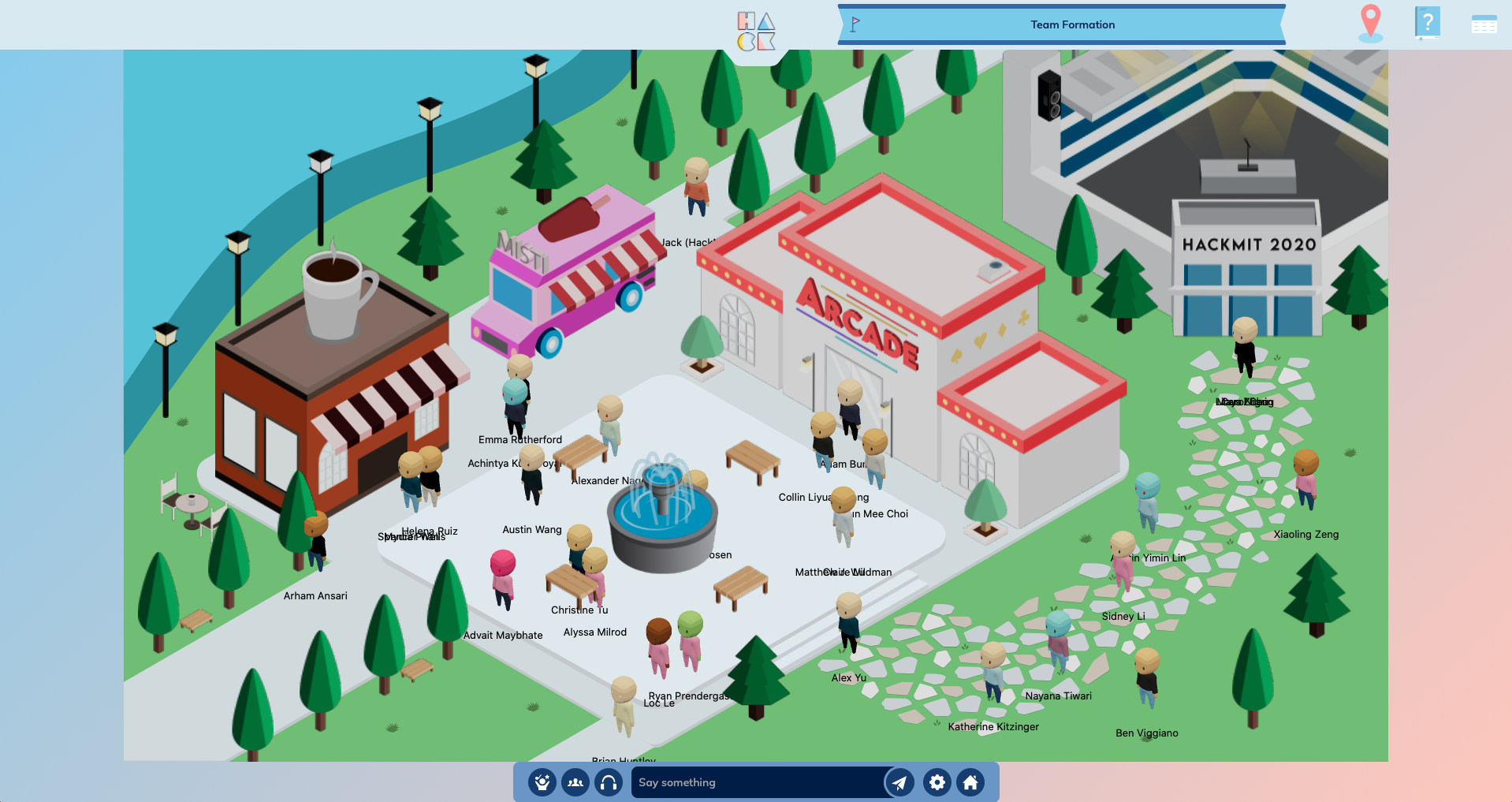

And here are a few screenshots from throughout the weekend:

I’ll probably write a separate post on more technical details about Hack Penguin, but in the end, our team designed and built an online isometric MMO-esque platform that had an enormous array of features, including:

- A “sponsor town” where each company had their own building, and hackers could enter buildings to talk to sponsor representatives

- 33 different rooms for hackers to explore, along with a bunch of hidden “easter eggs” and objects to interact with in each room

- Tents for each of our partnering nonprofits, featuring a variety of sources of inspiration for potential hackathon projects

- A mall with a fitting room where you could customize your character by changing the colors of your character’s skin and clothing

- A coffee shop with a world map, where hackers could pin where they were from

- An arena that hackers could join for “peer expo,” during which hackers met each other and learned about each other’s projects.

- The “jukebox,” where hackers could suggest songs that everyone would listen to together in real-time

- A custom 3D character model with 6 different dance moves that could be performed at any time

- A virtual version of TIM the beaver, our school’s mascot, that walked around and said things at random

- 10 different achievements for hackers to earn by participating in various parts of our event

- also we open sourced the whole thing!

I am honestly floored by how much work we got done over the summer, and the project could not have been completed without the collective work of 20(!) members of our team who made significant design and development contributions over the summer, along with everyone else on our team who planned all of the parts of our event. Our marketing and design team especially deserves a ton of credit considering that most of them had no experience with game design or isometric design at the start of the project! Despite the virtual format, we managed to ship HackMIT-branded swag to almost all of our hackers, judge every submitted project within a 2-hour time period on Sunday morning, and much, much more. I’m going to miss organizing HackMIT, and I can’t wait to see what the team puts together for HackMIT 2021. I can only hope they’ll be able to hold it on MIT’s campus.

Also, if you’re a hackathon organizer who needs any tips on planning a virtual hackathon, please get in touch with me or with our team!